A History of the Commodore 64 in Twelve Objects

Inspired by the BBC's A History of the World in 100 Objects, I posted A History of the C64 in Twelve Objects weekly from November 1st, 2024 to January 17th, 2025.

Object #1: The Commodore 64 itself

The Commodore 64 is known affectionately as the breadbox for its shape. Launched in 1982, following the Commodore company’s successful VIC-20 computer (1980). At 12,5 million units sold, the C64 was by far the best-selling home computer of the era, and it was also the platform with the most video games from 1985 to 1993 – 5,500 games are known.

But there is a mystery: there are both computer and video game histories that never mention the machine. My new book tries to find out why. I have tried to write the best book I could about the C64, but this was also my own first computer, and revisiting it has been thrilling and full of surprises.

The C64’s longevity went beyond any expectation – home computers were known to have a short life span, and already in 1983 Sierra game developer Ken Williams was spreading the rumor that production was about to cease, yet the machine was produced until 1994.

Strangely, none of its three central chips were originally designed for a computer. The 6510 (6502) CPU was originally planned for control systems, the SID sound chip was designed for synthesizers, and the VIC-II graphics chip was originally planned for video game devices. This became the C64, combining state-of-the art graphics and sound with strange flaws, such as a limited BASIC programming language and slow tape and disk drive.

Though Commodore never updated the machine functionally, users and developers fixed its flaws and kept finding new ways to use it. In the book, I call this the five lives of the machine. The European box shows the first life – a serious computer for work, studying, and the home, and for programming in BASIC.

Object #2: 10 PRINT “HELLO”: GOTO 10

Turning on the Commodore 64 launches us into a comforting interface in dark and light blue colors. It is a machine where interface, programming, and housekeeping take place using the same BASIC programming language. We can type immediate commands such as:

?10+20

30

READY.

BASIC (Beginner's All-Purpose Symbolic Code), originally developed by John Kemeny and Thomas Kurtz at Dartmouth College in the early 1960s, was designed to make computing universally accessible, at first for Dartmouth students. BASIC became a central platform for games in the 1960s and 1970s, and David Ahl's book BASIC Computer Games (1973) compiled and distributed the games made in computer labs on paper, the only viable form of mass-market program distribution of the time. One central early aspect of Commodore 64 culture was to type in pages and pages of programs from manuals, magazines, and books.

I think a core joy of programming is that we can make the computer do sustained work for us. The Commodore 64 User’s Guide coming with the machine encourages us to make a program printing “COMMODORE 64”, but the text was almost always the user’s name.

10 PRINT “HELLO!”:GOTO 10

Feel free to make your own 10 PRINT program in this emulator.

The next step was often to change the colors on the fly, and creatively making your mark on store or computer lab machines was an ongoing sport - a competition of ingenuity, speed, and presence:

10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1)); :POKE 646,RND(1)*16:GOTO 10

Writing programs like this, the one-liner, became an entire genre of programming onto itself. The User’s Guide also suggests this maze-making program, which randomly prints left- and right-leaning lines which form a maze on the computer screen:

10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1)); : GOTO 10

The book 10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1)); : GOTO 10 is dedicated to this program and discusses the history of one-liners. A more recent variation of the one-liner maze is here.

Later computers became easier to use, with icons, mouse, and windows, but the connection to programming was also lost, and today, sadly, computers no longer encourage us to fill the screen using small programs.

PS. Is 10 PRINT "HELLO!" an object? I think so!

Object #3: "We promise you won't use the Commodore 64 more than 24 Hours a Day" - advertising

Who is the Commodore 64 for? In the 1985 ad “We Promise you won’t use the Commodore 64 More than 24 Hours a Day”, the Commodore 64 is for the whole family, divided into familiar roles, and the machine guarantees the family’s safety and unity. Research assistant Laurel Carney at MIT pointed out that the text, “It’s 8 a.m. Do you know where your daughter is”, echoes a 1960s-80s US public service announcement scaring parents to keep tabs on the whereabouts of their children, “Do you know where your children are?” In the ad, worries about safety speaks for getting a computer – because the computer is so addictive, the whole family will be kept safely home, with dad (who seems to get very little sleep) doing both office work and stocks, the son playing games and doing homework, the younger daughter solving puzzles, the elder daughter studying the solar system, and mom looking up recipes and managing the household with a database.

Though Commodore lacked a global advertising strategy and left it to individual countries come up with their own, there was an early global pattern of focusing on the serious side of the C64, and only mentioning games as an aside.

Compare the previous ad to this: The best-known ad today is probably the Australian "Are you Keeping up with the Commodore", famous for its catchy jingle, with its implied threat that you will fall behind without this computer, and the bizarre hand gesture from the C64 users. (Source.)

In many European countries, Commodore gradually accepted the machine's status as a game computer and began to advertise it as such. This circa 1987 Swedish ad makes fun of apparently delinquent youths. "Where have you been? Out. What did you do? Nothing," with the C64 being the better alternative, young people enjoying playing video games together. The acceptance of games also made it into the C64 packaging, sometimes themed around bundled games like Batman.

Such computer ads also had the feature that the dedicated computer owner – like me! – liked the ads because it said positive things about their computer in a public space. I did feel aligned with the Commodore company at the time and wanted to see more and better C64 ads.

Object #4: Impossible Mission and Tapes

Another Visitor. Stay a while, stay forever!

The hammy voice of the evil scientist greets the player. The 1984 Impossible Mission by Dennis Caswell at Epyx was a technical marvel when it came out.

The “Another Visitor” sample and the “Destroy Him by Robots!” sample were shocking because the Commodore 64 did not have any facility for playing sampled sound. The sample was played by quickly changing the volume of the sound chip, creating clicks of different volume. The animation, based on pictures from a book about athletics, was fluid and expressive, combining multiple high-resolution sprites of different color.

Sound and graphics were amazing and high tech, exploiting and showcasing your C64’s abilities, making it the game you would show visiting friends to cement that yes, the C64 was the most advanced game platform.

The game, on the other hand, was painfully difficult. You die constantly by falling down, running out of time, or merely grazing an enemy robot. This was normal. Yet Impossible Mission was also inspired by Rogue, and the layout of the levels was randomized at every playthrough, which did not really become mainstream until the release of Spelunky in 2008.

Impossible Mission came on tapes or floppy disks. The exciting-looking box evoked sci-fi and the cold war and the pictures were – as everybody understood – nothing like the actual game. Inside the box was a manual, as was the custom, and the tape itself.

To play the game, you’d put the tape into Commodore Datasette deck, rewinding the tape before typing “LOAD” and pressing play.

(Photo by Evan-Amos, public domain).

Most users also had stacks of regular audio tapes onto which pirated software had been recorded, and the little counter on the Datasette was paramount for finding the location where the game was stored, noting the location on the tape inlay. If you had a tape deck, you would do this a lot.

(Imgur)

Some radio stations even broadcast C64 programs on air, giving a wall of modem-like screeches to be recorded on a regular tape recorder, and then inserted in the Datasette.

Object #5: Zzap!64 and other Magazines

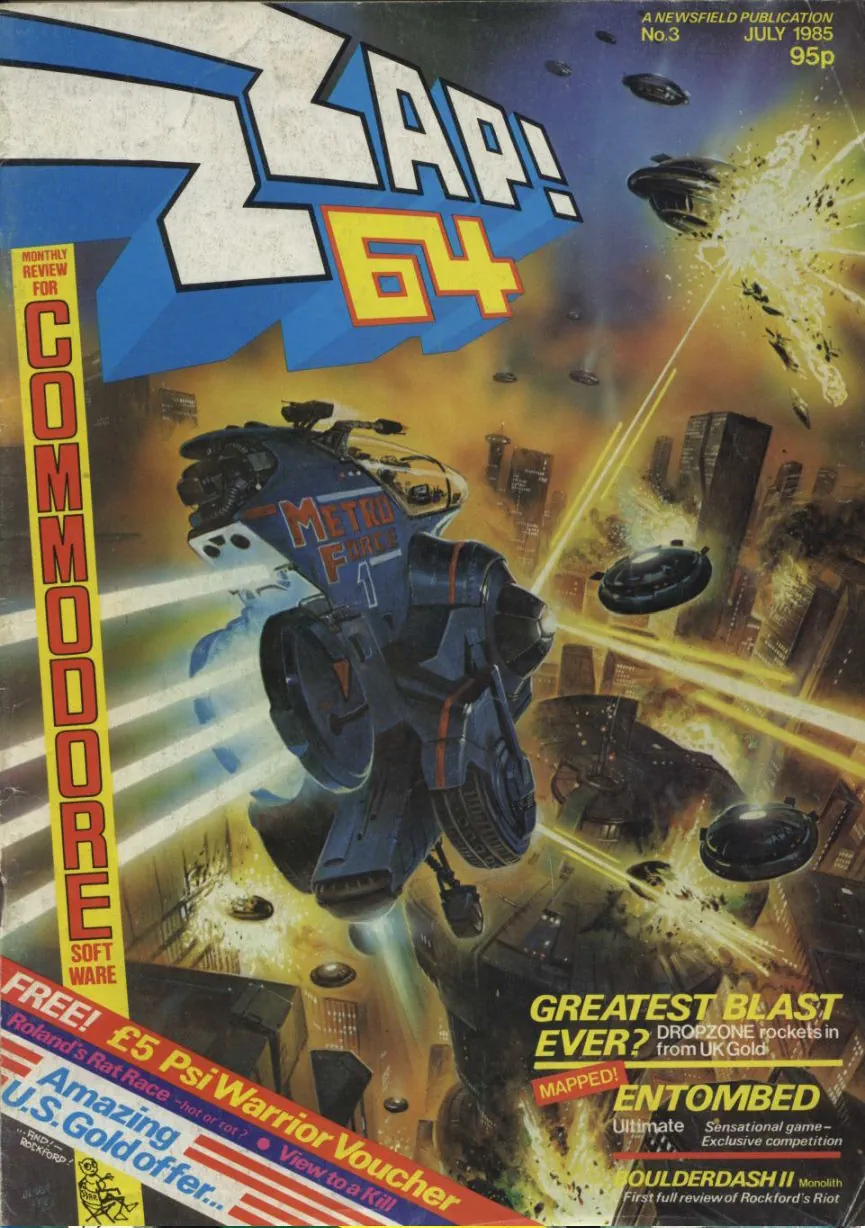

On the magazine cover, a spaceship swoops across the glowing city, laser beams across the sky summarily disposing of enemy crafts. Zzap!64 was the preeminent UK Commodore 64 game magazine, launched in 1985, published until 1994 ( “Commodore Force” in the end), and reanimated as commemorative issues and annuals from 2002 and onwards.

Early covers, by artist Oliver Frey, borrowed from the world of fantasy posters, obviously not referring to the actual images on the computer screen, but to the imagined worlds of games and computers. Frey’s covers often commented on the games reviewed (as in Dropzone on this cover).

Why magazines? Obviously pre-internet, and absent widespread use of BBSs, magazines were the news sources and the public sphere of games and computers. At launch, Zzap!64 declared itself to be a pure C64 game magazine free of four things: free of other computers, non-game applications, nerdy programming, and type-in program listings. (All made their way into the magazine over the years.)

Loved for its cheeky, very UK irreverence where it is impossible to write even a single image caption without some twist, the magazine promoted its young reviewers, whose cartoon images would appear with speech bubbles, giving personal and sometimes contradicting opinions on games.

Commodore 64 games were usually so challenging as to be impossible – playtesting was not yet formalized or required – and especially European magazines regularly published cheat codes in the form of programs and POKEs that would modify the game program, making the games playable and completeable after all.

US Compute’s Gazette (1993-1990/95) was the magazine for the serious computer user – accommodating games, yes, but neither giving too much space to game reviews, nor going overboard with technical tricks. I think of Compute’s Gazette as the truly respectable of the magazines here.

German 64’er Magazin (1984-1996) was also a general C64 magazine, covering everything from word processors (“how to use the C64 instead of a typewriter”) to music, games, and programming. 64’er was far more technical than Zzap!64 or Compute’s Gazette, covering the demoscene, discussing graphical tricks in detail, and featuring classified ads that early on offered clearly pirated software.

As the only viable mass distribution channel for software, 1980s magazines featured interminable program listings for the user to type in, offering free software at the cost of typing and proofreading, but also offering the bonus of learning about programming.

Magazines were your source for what was going on, for what to buy, how to program, how to talk about the games, and how to cheat.

Object #6: Wizball and other Scrolling Games

What even is the 1987 game Wizball (Sensible Software)? With glowing reviews and a spot on many “best C64 games ever”-lists, in this game you are a wizard wrapped in a ball, at first hard to control, but gradually acquiring new skills and a cat companion. The world has lost its color, and your job is to collect colors, making the world whole and properly saturated.

Like many early C64 games, it is unclear what genre the game belongs to. This horizontally scrolling game is a bit like Defender in its shooting, but more like an action-adventure platformer in the way you traverse the world and collect objects. Like other C64 games, it is famous for its music, this one by Martin Galway.

The Commodore 64 came out in 1982, and the first smoothly scrolling games followed in 1983 (International Soccer, Son of Blagger, Neoclyps, and Wanted: Monty Mole). When did PCs have smoothly scrolling games then? This is usually said to be ID Software’s 1990 Commander Keen. IBM appears to have made a conscious decision not to add game-related features, and hence THE PC WAS NEARLY A DECADE BEHIND.

Along with the Atari 8-bit computers, the C64 could do what its main competitors (ZX Spectrum, Apple II, IBM PC, Amstrad) could not: The C64 video chip, the VIC-II, allowed for games that smoothly scrolled around a larger world. “Scrolling” is not a genre today, but the scrolling facility allowed for the early C64 tradition of action-adventure games and action-adventure platformers (predating say Nintendo’s games by many years).

The 1983 Wanted: Monty Mole instructed players to REMEMBER IT’S NOT JUST A PLATFORM GAME ITS AN ADVENTURE, emphasizing the newness of combining action with exploration. The C64 hardware thus enabled a whole subgenre of action-adventure games.

When European developers later made games of open exploration, say Grand Theft Auto, it was not surprising, as these were the kind of games they had grown up on.

What scrolling games do you remember?

Object #7: The SID Chip – Commodore 64 Music

It is said that writing about music is like dancing about architecture, but nevertheless: The 6581 SID (Sound Interface Device) chip of the Commodore 64 was designed by Robert Yannes in 1981. According to Yannes, he was inspired primarily by synthesizers, hoping to create a chip for use in other musical instruments.

In practice, the SID chip became the sound chip of the Commodore 64 and has the magical quality that it still sounds modern after 43 years. Why? Because it encapsulates the classic analog synth sound of simple waveforms (pulse, triangle, sawtooth, noise) played with an ADSR envelope, controlling the fade in and out of a particular note. There are also filters and ring modulation facility. The SID chip was an unusual combination of digital and analog components, and different versions and individual chips sound different. Just like analog synthesizers.

Though Yannes had hoped for more voices, time and physical constraints reduced the 6581 to three simultaneous voices (though developers later figured out how to play samples as well). The limited voices gave C64 music its characteristic fast and rhythmic arpeggio style, where chords are played by quickly playing its constituent notes in turn.

Oscilloscope view of Rob Hubbard’s Monty on the Run music. (Source: Rolf Bakke.)

Rob Hubbard’s Monty on the Run music is among the more famous pieces of C64 music, developing over time, and switching between impressions of different instruments. European video game orchestra events will often include Monty on the Run.

Danish Broadcasting Corporation Symphony Orchestra C64 game medley

As C64 programming advanced, the famous composers, including Rob Hubbard, Jeroen Tell, Chris Hülsbeck, Ben Daglish, and Johannes Bjerregaard, learned to modify the properties of the individual voice on the fly, such that a given note could be a combination of multiple waveforms, or perhaps pitch bend or feature vibrato. As the image shows, individual voices were used to combine many waveforms, giving the expressive quality of later C64 music.

C64 game music was also distributed separately, ripped, from the original games they came from, and the C64 thus served as a media distribution platform before there was anything like MP3s.

Object #8: Floppy disk (with pirated games)

These two floppy disks came with a second-hand Commodore 64. Such flat objects for storing programs were called “floppies” because they were easily bendable, as opposed to fixed disks, and hence quite fragile. 5 ¼” was a common type of floppy disk, shared with IBM PCs and many other computers. As was common, this second-hand C64 had a collection of disks (twenty) with pirated material, and only two pieces of original software.

The 1541 disk drive. Photo by Evan-Amos.

Compared to tapes, such disks were the more expensive storage option for C64s, the 1541 disk drive often costing as much as the computer ![]() itself. Already with their first computer, the PET, Commodore had decided that devices should be connected to computers using USB-like cables, rather than through opening the computer and installing hardware. This was an elegant and surprisingly modern solution but also made the devices quite expensive, as they needed to be small computers by themselves.

itself. Already with their first computer, the PET, Commodore had decided that devices should be connected to computers using USB-like cables, rather than through opening the computer and installing hardware. This was an elegant and surprisingly modern solution but also made the devices quite expensive, as they needed to be small computers by themselves.

To read the fragile disks, the 1541 disk drive often needed to do a “head alignment”, where the disk drive adjusted itself by banging the head against an internal stop, giving a surprisingly violent loud sound. To be a C64 disk drive owner was to live with and listen to the recurring sounds of the drive.

According to the label on these particular floppy disks, the disks originated from a course in WordPerfect for IBM PCs (“WP Kursus” 1-2) and were only later appropriated for less "serious" C64 use. The paper sleeve lists the software: Donald Duck’s Playground, Duck Shoot, Falcon Patrol, Frogger, Ghost ‘n Goblins, Grand Prix. Piracy was pervasive on the C64.

There were two types of floppy disks: single- and double sided, the latter being more expensive, but it quickly became known that you could cut a little notch in the side of a floppy, allowing you to use both sides of the cheap disk.

This was part of the impetus behind this history of the C64 through objects : Owning a C64 was an intensely tangible & physical activity. With floppy disks, to be a C64 owner was also to be adept with scissors.

Object #9: Final Cartridge - Fixing the C64's Flaws

It wasn’t all great. The Commodore 64 came with glaring, everyday gnawing flaws that Commodore never fixed:

- The tape drive was slow.

- After a series of unfortunate events, bugs, bug fixes, workarounds, and last-minute botches in the production process, the C64’s disk drive was not slow, more like glacial.

- C64 BASIC lacked proper commands for dealing with the disk drive, and even seeing the contents of a floppy involved the LOAD “$”,8 command, erasing the current program in memory.

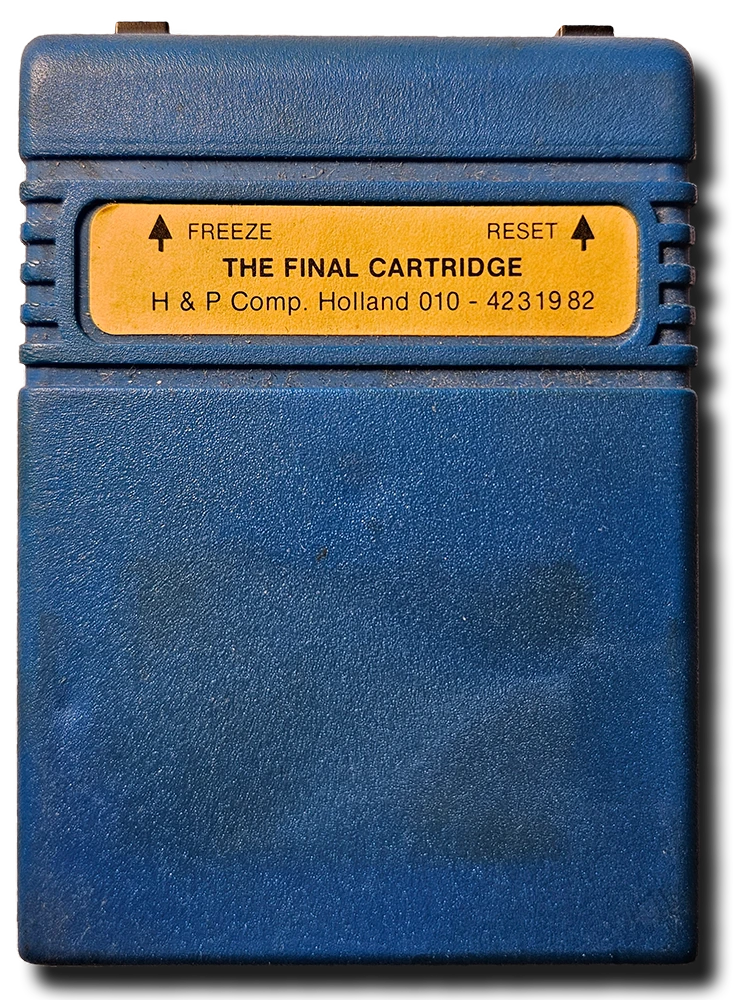

The 1985 Final Cartridge was your solution to these flaws, creating a new tape format, speeding up the disk drive, adding new BASIC commands and utilizing the function keys (F7 to show the floppy directory).

In today’s parlance, Final Cartridge was a monumental quality of life upgrade. You could already do almost everything without the cartridge, but the cartridge made life easier and faster, allowing you to quickly shuffle between disks, make copies, modify programs, or just load games faster.

Final Cartridge’s additional features also accommodated technically minded user:

- A machine code monitor for reading and modifying the program in memory.

- A reset button.

- A “freeze” button (in later iterations) for ostensibly backups, or even saving your game progress in games that lacked suck a function.

- Better printer support.

How could you make the disk drive faster? You might expect that the bottleneck was reading and writing the floppy disk itself, but that was already plenty fast. The bottleneck was communicating the data over the cable between the C64 and the drive. The disk drive could be sped up because the 1541 disk drive is a small computer of its own, and because there are disk commands for sending small programs to the drive. A fast loader like Final Cartridge thus sends a program to the drive with a faster “protocol,” a faster way to send data between computer and drive.

Did the Final Cartridge make the C64 everything it would have been with more development time and a higher price? Perhaps, but there was a joy in plugging in the cartridge for the first time, making your computer faster, nicer, and more enjoyable.

Object #10: You are Invited to a Demo Party

I have been telling this Commodore 64 history through objects. And indeed, the C64’s commercial life ended before the immaterial internet became widely available. Though dial-up bulletin boards (BBS) gradually made it possible to communicate over telephone lines, the more or less underground (and more or less illicit) technical culture of the C64 was tangible and completely physical.

Parties started taking place during the late 1980s especially in Northern Europe, meetings of almost exclusively boys and young men bringing their computers and CRT monitors to crowded rooms, sharing software, and later competing in making demos, audiovisual programs demonstrating skills. The first parties were strictly noncommercial and invite-only events. You felt part of an elite club, receiving the paper invite by physical mail.

Looking back, the bigger parties started in smaller towns, using municipal buildings like schools and community centers as well as support from non-profits like scouts. The 1988 Tommerup party was in the latter, a scout center. According to legend, organizers were overwhelmed by attendees, and the party was moved to an also overcrowded community center.

The 1988 Tommerup party in a much too crowded room. (Photo by Björn Fogelberg)

As I began participating in such events around 1988, parties tried to shed the association with piracy and became “demoparties” with formalized competitions for the best demo.

New Limits demo by The Supply Team

In Too Much Fun I tell the story of a 1989 demoparty, what it was like to write demos and to participate, but for now it is enough to say that early demos were often focused on showing one technical trick, like in The Supply Team’s New Limits demo released at Tommerup, which shows a scrolling text that fills the entire screen including the border.

Crest/Oxyron’s 2000 Deus Ex Machina demo first elegantly transitioning from the blue desktop, then showing rotating 3d

Demos later evolved into more elaborate designs, often structured around a theme or visual composition, like in Crest/Oxyron’s 2000 Deus Ex Machina.

Which demos have you enjoyed?

Object #11: Turrican II - Keeping up with the Amiga

The final boss in Turrican II for the Commodore Amiga (source)

By 1991, the Commodore 64 was waning as a commercial platform - yet games were still coming out, especially in Europe. There had been little reason to expect that the C64 would be produced for so many years, and Commodore had assumed that the Commodore Amiga would be the replacement.

Launched as a professional computer in 1985 (Amiga 1000) and later as a consumer model in 1987 (Amiga 500), the Amiga was technologically in a completely different league. Designed by Jay Miner and the team behind Atari’s 8-bit computers, the Amiga had a faster CPU, digitized sound, a graphical multitasking OS, and a graphics system geared towards hires, multilayered and fast-moving graphics.

Where the original 1990 Turrican was a C64-first release, Turrican II was released in 1991 for the Amiga and later for the C64, PC, and other platforms. According to interviews with developer Manfred Trenz, Turrican II development started on the C64, but this platform apparently was no longer the primary focus. In this way, the space between Turrican I and II is the moment where the C64 became the secondary platform for the developer. The Turrican games also mark the time where the C64 action-adventure tradition discussed previously became influenced by Japanese action games too.

How would the C64 version stack up to other platforms? As the Zzap!64 review stated, “This game is the sort of program you’d expect … on some exotic, super expensive Japanese console. … The walkers are terrific too, they look like Amiga characters”. While the hardware of competing platforms was improving, C64 developers were also improving their skills, sometimes with inspiration from the demoscene.

Final boss in Turrican II for the Commodore 64 (source)

Developers were trying to keep up with more capable platforms, especially with the Amiga. In C64 reviews, the recurring question in the late 1980s and early 1990s became, “how good is it, compared to the Amiga version?” - or to a newer computer or console? This was raised for games (Defender of the Crown, Lemmings), user interfaces (the graphical GEOS interface), and demos.

In Too Much Fun, I call this the Fourth Life of the C64, characterized by anxiety about the status of the machine. But that anxiety was to dissipate, as I will discuss next week.

Object #12: The Commodordion – two C64s = one accordion

Linus Åkesson's Commodordion

The final object: In the very first post of this “History of the Commodore 64 in Twelve Objects” series, I talked about the Commodore 64 itself - the iconic beige machine. Since then, I have explored ten other objects, from games and floppy disks to cartridges, BASIC programming, music, magazines, and even a paper invitation to a demo party.

It is now 43 years since the Commodore 64 was introduced at the 1982 Consumer Electronics Show. Amazingly, it went on sale the same year as the first CD player.

The C64 is now a historical device, but its story isn’t over. Users and developers are still finding new uses for it. When I started writing Too Much Fun in 2022, the charts for best demos and best games on CSDb and Lemon64 were dominated by old releases. Today, most top spots belong to new creations. There is a real resurgence of activity on the Commodore 64.

There also is a culture of Commodore 64 hardware experimentation. For my final object, I choose Swedish hardware hacker and musician Linus Åkesson’s 2022 Commodordion. It is a charming, musical, technically impressive, and obviously absurd project, making an accordion by combining two C64s connected by a bellows constructed from floppy disks.

Åkesson’s work exemplifies the continued fascination with the C64. It is about discovering new tricks and properties of the C64, Amiga, and other hardware, it is about programming expansive and minimal demos, making new hardware. Here the hardware is sometimes musical instruments used for musical performances.

Of course, the C64's resurgence is also fueled by the availability of high-quality emulators. As I discuss in Too Much Fun, you can now experience the C64 without needing the original hardware. But this easy access makes projects like the Commodordion even more appealing, a way to connect with the physicality of the machine and experience it in a completely new way.

What song is the Commodordion playing? Ragtime tune Maple Leaf Rag by Scott Joplin, which has its own C64 history as music for excruciatingly difficult game China Miner.

The Commodordion symbolizes how exploring the Commodore 64 today is not just nostalgia. The C64 makes us think about forgotten pasts, about our current relationship to technology (do we always need to upgrade?), and through the C64 we can blend ideas from different eras to create something entirely new.

Thank you for reading

Jesper Juul

Copenhagen, November 2024-January 2025