This is my fourth Patch Wednesday post where I discuss a question about video games that I think is unanswered, unexplored, or simply not posed yet. I will propose my own tentative ideas, and invite comments.

The header sounds a bit like Ash Wednesday, so we can reaffirm our faith in the idea of examining video games, but Patch Wednesday to mark the sometimes ragtag and improvised character of video game studies.

Where did Threes come from? The currently massively popular puzzle game Threes is seen as the victim of a large number of clones, particularly 2048. To prove their point, the developers have posted a long article explaining their design process.

At the same time, though 2048 is in many ways similar to Threes, some people also whisper that they think 2048 is the better game, because it is simpler (always doubling 2, 4, 8 rather than the 1+2=3 merging of Threes). It certainly is more intuitive to a programming mind.

Life is not fair, of course, and it seems a shame that someone can borrow from the game that someone else developed and through a minor change reap the seeds of the iterative design process of someone else. But you cannot copyright game ideas, only their expression.

Regardless, where does Threes come from? As a headline, the game contains two particular and rare mechanics: merging (the combination of objects to form higher-level objects) and slide-to-combine (pushing the entire screen to one side at a time, combining objects that are pushed into each other).

1) Merging

The merging mechanic does at this time seem to be inspired by Triple Town, where merging is reminiscent of match-three games. Yet where regular match-three matches lead to clearing the objects matched, Triple Town matches always creates a new higher-level object.

But where does this merging mechanic come from? Dan Cook, triple town developer stated that it was inspired by the idea of sets in card games as well as by crafting systems.

Quick research and the twittersphere proposed a few sources for merging:

The king in Checkers – but this is not what I meant, since the stacking of two pieces is just a convenient way to signal a special piece, rather than an element of the gameplay. So merging is to be understood in a gameplay-sense.

The king in Checkers – but this is not what I meant, since the stacking of two pieces is just a convenient way to signal a special piece, rather than an element of the gameplay. So merging is to be understood in a gameplay-sense.- Combining stones in Mancala – again, I had to realize that this was not what I meant, and had to narrow down the concept of merging: merging should be unidirectional, as in the player being unable to take apart the merged object.

- Dan Cook’s suggestion of sets in card game was also not what I meant by merging, since sets are (generally) immediately removed from a game.

- A similar objection applies to the suggestion that melds in Gin Rummy are a type of merging, since melds do not become separate entities.

- Aaron Isaksen reminded be that he had shown me his chip-merging game Chip Chain game (2012).

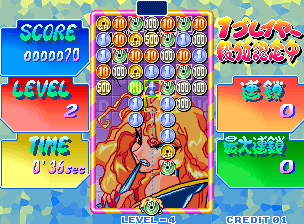

- A promising candidate for a first merging-game is Money Puzzle Exchanger (1997) where you can combine yen coins into higher denominations.

- Dan Cook also suggested that the powerups in Bejeweled 2 (2004) are actually a type of merging. We may not think of it as merging because the default response to a match (three) is for the tiles to disappear. On the other hand, high-level match-three playing is quite similar to Triple Town in the requirement for planning the location of the generated powerups.

- A non-puzzle example is the Archon in StarCraft (1998), created from two high templars.

- And crafting, of course, but is it the same, or is it too much about managing inventory items and too little about what’s on the screen? If it is the same, then we may have to dive into the history of D&D (Jon Peterson’s Playing at the World would be a place to start.)

- (

Winner)But then I was pointed to the 1996 Mouja, which also features merging of coins. As far as I can tell this is the first puzzle game to use merging, but on the other hand this also seems unlikely, given how simple a mechanic merging is.  New winner (thanks to Marc Majcher): the 1990 Darwin’s Dilemma.

New winner (thanks to Marc Majcher): the 1990 Darwin’s Dilemma.- For analog games, Cassino (ca. 1797) is a candidate, given the focus on building card stacks that act as one card.

I am sure I have missed something here (let me know). Until I came upon Cassino (which I played as a child), I was entertaining the theory that merging is simpler to do in digital form, and therefore was rare in analog games, but this theory is probably wrong.

2) Slide to combine

(Winner) T![DBTPlay07[1]](http://www.jesperjuul.net/ludologist/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/DBTPlay071.jpg) his was easy: I immediately recognized the slide to combine control of Denki Blocks (2001). In Denki Blocks, objects don’t merge to occupy a shared space, but rather become stuck to each other.

his was easy: I immediately recognized the slide to combine control of Denki Blocks (2001). In Denki Blocks, objects don’t merge to occupy a shared space, but rather become stuck to each other.

Is there an earlier one?

What we’ve learned

The “first game to x” is not be as simple as it sounds. In this case, the concept of merging had to be defined more clearly before I could start tracing it. Slide to combine only had one obvious candidate.

Finding the “first” is very hard, since you can never prove your argument, only hope not to be disproved.

Note that the Threes developers have (as far as I know) not mentioned any of the games I have cited as sources for merging and sliding. I think some of this is due to a particular mechanic simply being “in the air”, and some of it may be parallel invention. In many cases, we will never know.

Games are made out of bits of other games, people!

Thanks

To Eric Zimmerman, Frank Lantz, Dan Cook, Alexandre Houdent, Aaron Isaksen, Bruce Boyden, Mikkel Faurholm, Clay Branch, Matthijs Holter, Marc Majcher.

A lovely look at some similar systems in past games.

The historical approach to understanding game design can be somewhat fruitful, but as you’ve noticed, it falls down more often than not.

One thing that is very true about both Threes and Triple Town is that they they use similar math (linear crafting trees involving multiples of a single ingredient which results in an exponential cost curve for higher order pieces). Both games stumbled upon this after extensive experimentation and without referencing external games (at least not consciously…and many of the examples you list are uncommon titles that spread weakly. Mancala and Checkers are of course more common, but of questionable linkage.)

So another way of looking at games is that they are functional logical structures. Certain types of math may be invented independently of one another without a distinct cultural inspiration because…that is how the physical and logical universe works. Only certain machine operate on the human mind in the desired fashion and as soon as you start exploring the space with a given fitness criteria, you’ll end up with quite similar systemic elements.

The cultural / historical perspective isn’t purely bullshit, but is it at best one specific surface viewpoint on game design that has surprisingly little to do with the nuts and bolt iteration and testing of new designs. A description of a watchmaker’s craft via third hand accounts. What is involved in inventing working machines? Many teams take even ‘proven’ designs and find they need to rework them to their core to really get them functioning as desired. The work is more about math and structure and the nearly scientific method of testing experimental rules on human subjects.

All the best,

Danc.

The earliest digital version of the combining mechanic you’re talking about is Darwin’s Dilemma, in 1990.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Darwin's_Dilemma

@danc I agree that there are certain logical structures that operate, and that facilitate a type of simultaneous discovery as you suggest. Here I was looking for the earliest examples which is distinct from asking whether someone was actually inspired by a particular game.

At the other end, we have well-defined genres such as shooters and match-three where it is clear that developers (and the audience) are aware of earlier instantiations of the mechanics that they are using. This is clearly part of the nuts and bolts of the majority of game development.

What is hard is telling the difference between the two extremes.

@Marc Wow, didn’t know that. We have a new winner.

Well, beware practicing verificationism. Videogames are necessarily logical and mathematical in one sense, to the extent that they are programmed to run on computers. But in the sense that the gameplay itself in both Triple Town and Threes can be described as logical and mathematical…sort of.

It’s one way to describe the gameplay, and I mention verificationism because if you’re looking to describe the gameplay in a mathematical fashion then you’re going to find that it works.

But, as you mention, games require experimentation to find some sort of balance between what the designer can try to objectively create and what it is assumed players will subjectively experience. Mathematics doesn’t function like this – if these games could be reliably described logically, no experimentation would be necessary. That is to say, we can describe these games mathematically but I don’t think it’s correct to say that it is driving the design. Essentially, we can perhaps model these games mathematically and this is a useful description, but the model shouldn’t be mistaken for the real thing.

ie. We can’t try to say that “linear crafting trees involving multiples of a single ingredient which results in an exponential cost curve for higher order pieces” make people have fun. I think that’s essentially a category mistake. Like describing thousands of lines of good netcode and saying “this is what a good online experience feels like”.

It’s also quite different from scientific experimentation in that what we’re looking for in the end is whatever we decide we’re looking for – in a way we are inherently verificationist in this way. A game is designed until it feels correct, and I don’t think it’s especially helpful to invoke science here. Trying again and again is obviously a good process for any work, but that process is very different when comparing particle physics to creating a game board.

@Nick You are of course correct. Games merely use math and the process is closer to engineering than it is to pure scientific research. The physical reality we are dealing with is the intersection between the human machine (brain, body, psychology), the physical machine (buttons, screens, etc) and algorithmic machine (code, math)

Much like in other functional disciplines, you see disparate group arriving at similar solutions. Doors for example across cultures tend to be of a certain minimum size and vertical orientation. That’s the engineering design that fits the human body.

I’m intentionally using engineering language because outside of game development it is a perspective I rarely see treated intelligibly. Much of what is written about games and their cultural roots comes from gamers looking in at a distance, imagining how things might be done. Much of it comes from a media-centric perspective which tends to ignore the strong functional and utilitarian constraints of game building. 90% of my game design process is inventing new doors that humans can physically walk through. 10% is the historical influences. If games were anything close to a book, 99% of the effort would be spent merely figuring out how to turn the page.

I’d argue that even in the case of FPS and other well defined genres, the internal process of development is more akin to an industrialist copying a product design for a product category. A small scooter is popular so someone reverse engineers the design to create their own. In the process, they change the logo and the color and perhaps some minor body shapes. Certainly such a lineage is worth studying from a product history perspective. However, it is also useful to ask what key engineering aspects produced the desired functionality (a more efficient 2-stroke engine, crowded city streets, a new tax on fuel)

Those are fascinating design discussions that happen perhaps too rarely.

Make sure to check out Monsters ate my Condo (iOS) as well. This game has a quite simple combining/merging mechanic by removing objects from a stack.

@Pim Ah, good point.

Interesting perspective and history. I think some of the question to deal with here is how far you bend the analagous gameplay to fit with a predecessor and when you decide to draw a boundary and see it as something different/new. Such definition boundaries are always tricky and never clear. While not “slide to merge” specifically, Snake is a game whose entire gameplay is about merging. Physical, playground games are worth examining as precedents too. Games like British Bulldog and various tag/team games often require capturing and merging players into a team. A conga line is also merging play, if not a game.

@Andy Yes, that is the big question. We have clear examples of inspiration such as Threes to 2048, Bejeweled through to Candy Crush, the idea of shooting opponents in confined hallways.

Outside that, I agree is quickly becomes blurry. It is also a question of formulating what exactly we mean by “inspiration” or “similarity”.

I hadn’t thought about tag games, and especially not conga lines.

Another line of questioning would be how common such logical operations are outside games. Adding an item to a set (even putting something in a bag) is quite common. Putting two objects together and transforming them into something new is common in math (2+2=4), but less so in the Triple Town sense of qualitative transformations.

Just as a matter of interest, why did you want to know the “first” game with the merging mechanic? That doesn’t tell you where 2048 or Threes got it. This is the kind of mechanic that has probably been invented independently hundreds of times throughout history. People could have been playing games that used it for centuries in remote parts of the world, but that doesn’t mean Threes was in any way inspired by them.

What you want isn’t the first example of the use of the mechanic: what you want is the progenitor game of the mechanic for Threes. Trace the family tree of Threes backwards and stop when you get to some game where the mechanic was apparently plucked from thin air. I doubt it would be Cassino, but then there’s probably a merging game or two in China that predate it by a millennium that haven’t had any impact on Threes either.

Just because something was first, that doesn’t mean that everything else is a descendant of it.

@Richard We agree – I do distinguish between a) identifying the first instance of x, and b) asking whether that first instance was the inspiration for subsequent instances of x or not.

Why do I ask such questions? I think it is interesting to examine different examples and to ask questions a) and b), because it teaches us how game history operates.