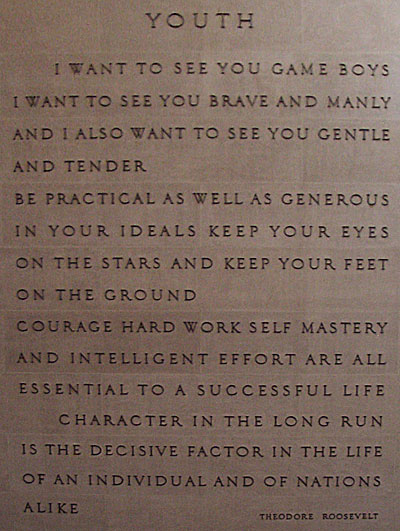

Not too important: I went to the American Museum of Natural History. The entrance hall features a few (physically) large quotes by Theodore Roosevelt. He wants to see you game boys.

Speaking at Georgia Tech, October 19th at 4:30

I am giving a talk at Georgia Tech this Thursday at 4:30Pm, in the Skiles building, room 010.

Talk title: “A Game in the Hands of a Player. Or: This Game is just like that Other Game.”

In this talk, I will look at the space between the game and the player. What happens when a player picks up a game, and how can game design influence the player’s actions and experiences?

I see this as an open field between basic two observations: 1) Different players may play the same game differently, and experience the same game differently. 2) Different games yield give different kinds of pleasures.

Books You Should Read

If you’re in the game industry, Ernest Adams has made a list of 50 books you should read. It’s at Next-Gen.

It’s an excellent list – OK, so Half-Real is on it – lots of breadth, so many things to go into.

For design, I really would put Tracy Fullerton’s (et.al.) Game Design Workshop on the list though.

Immature designers imitate; mature designers steal.

I am finishing an article on matching tile games, and the question of imitation and originality keeps coming up. I’ve often heard the idea of “the bad artist imitating, the good artist stealing” attributed to Picasso, but it is actually from T.S. Eliot in a 1922 essay:

Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different. The good poet welds his theft into a whole of feeling which is unique, utterly different from that from which it was torn; the bad poet throws it into something which has no cohesion. A good poet will usually borrow from authors remote in time, or alien in language, or diverse in interest.

Spot on for game design: The good designer welds his or her theft into a whole of feeling which is unique, utterly different from that from which it was torn; the bad designer throws it into something which has no cohesion.

Gizmondo IS WarioWare

Wired has the spectacular story of the thoroughly failed Gizmondo game system and the very shady Bo Stefan Eriksson: How a former Swedish debt collector and criminal managed to lure amazing amounts of money from investors in order to launch a doomed portable game device.

This is the story: Dubious character realizes that there are lots of money to me made in video games, invites equally dubious and video game ignorant friends along to make it big, launches terrible games.

I can’t be the only one to think that this is also the story of WarioWare, with Eriksson playing the role of Wario (or vice versa). Life imitates art. (Or vice versa.)

The difference being, of course, that the WarioWare games are sufficiently bad to be really, really good.

Pac-Man. Excel.

Seems we have an “unbelievable implementations of Pac-Man” week, so here is … Pac-Man in an Excel spreadsheet.

Ghost Cricket Pac-Man

Research answering a seldomly posed question: What happens if you let real insects control the ghosts in a game of Pac-Man?

This: Animal Controlled Computer Games: Playing Pac-Man against Real Crickets.

My feeling is that game balancing could be improved by selective breeding of the crickets, which I hope Wim van Eck will have time for in a future project.

Come out and Play in New York City

I am fortunate enough to be in New York for the very exciting Come out and Play festival of street games, so will be spending much of the weekend running around Manhattan.

I will also be participating in a panel with Frank Lantz, Jane McGonigal, Jesper Juul, Roy Kozlovsky, Franz Aliquo, and Nick Fortugno (this is sitting down, I presume) at 7PM on Saturday @ Eyebeam, “What are street/big/pervasive games anyway?“.