This is my fourteenth monthly Patch Wednesday post where I discuss a question about video games that I think is unanswered, unexplored, or not posed yet. I will propose my own tentative ideas and invite comments.

The series is called Patch Wednesday to mark the sometimes ragtag and improvised character of video game studies.

What is a game?

One of the joys of having been around for a while in game studies is to see certain arguments repeatedly go in and out of fashion. It’s not as much cyclical (since we never quite return to a place we have been before), but rather that old arguments come back, donning new garb and meaning something somewhat different than they used to.

At the very good recent DiGRA conference in Lüneburg, many speakers stated how they were “not interested in definitions”. After initially trying to question that sentiment, I decided to rather note some of the recent history of game definitions. Please pardon the self-indulgence as I return to my own earlier work.

*

As you recall, Wittgenstein argued against trying to define games (or rather the German Spiel), saying that we should not look for an essential core, but see the myriad ways in which the word is used, only connected by family resemblances. Or rather: in common interpretations[1], games was just an example for Wittgenstein – what he criticizes is the attempt at looking for definitions in the first place, for any word. So Wittgenstein’s argument is not specific to games at all.

The thing, of course, is that Wittgenstein is not trying very hard to find any commonalities in the activities he is describing (board-games, card-games, ball-games, Olympic games). At the very least, they do seem to be semi-repeatable activities performed by humans…

*

And then – certainly there is a general post-structuralist attitude common in the humanities and social sciences today, and which I was trained in myself. So when thinking about video games, it was interesting to try to make game definitions, in part because you are not supposed to!

In my 2003 paper The Game, the Player, the World: Looking for a Heart of Gameness I came up with what I called The Classic Game Model:

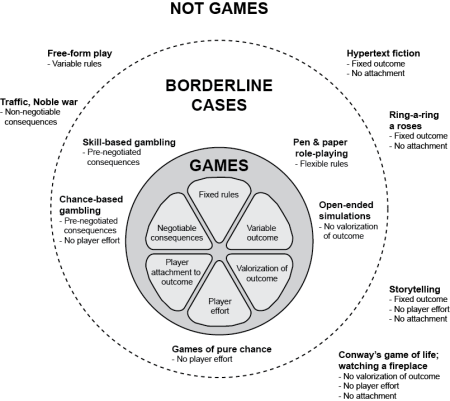

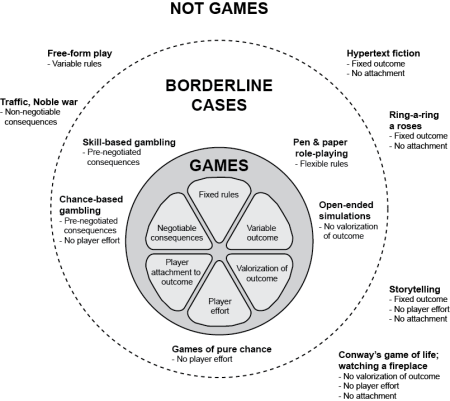

A [classic] game is a rule-based formal system with a variable and quantifiable outcome, where different outcomes are assigned different values, the player exerts effort in order to influence the outcome, the player feels attached to the outcome, and the consequences of the activity are optional and negotiable.

It also came with an illustration, pointing to the “games” where we tend to disagree about whether or not they are games:

What kind of definition?

I called this a definition, but what does that mean? It does not cover all possible uses for the word “game”, or even a (harder to define) preexisting notion of “game”. Philosopher Anil Gupta distinguishes between different types of definitions, let me mention three candidates[2]:

- Stipulative: “imparts a meaning to the defined term, and involves no commitment that the assigned meaning agrees with prior uses (if any) of the term”.

- Descriptive: “like stipulative ones, spell out meaning, but they also aim to be adequate to existing usage.”

- Explicative: “An explication aims to respect some central uses of a term but is stipulative on others. The explication may be offered as an absolute improvement of an existing, imperfect concept. Or, it may be offered as a “good thing to mean” by the term in a specific context for a particular purpose.”

This explains it better than I could: my game definition is not about covering all existing usages (descriptive), but it is still invested in previous uses (not stipulative).

Hence, my definition is explicative: it is intended as an improvement over an existing concept, but doesn’t aim to replace or supersede existing or future uses. It is rather a definition for the particular purpose of identifying points of contention around games.

An open definition

It’s an explicative definition, but it is also open in two ways:

- It is a “classic model”: it describes a model that was dominant a particular period in time, and this makes it useful for noticing when our conception of games By now, it seems clear that Sims and Sim City are games, but it wasn’t the case when they came out. Similarly, we can discuss why some people reject Proteus as a game.

- The definition is open to disagreements about borderline cases (gambling, P&P RPG, open-ended simulations).

Definitions: Limiting or liberating?

As I said, I think we are in a general post-structural epoch wherein it is easy to think of definitions as limiting, or even dangerous. The latter view arguably comes in part from Foucault, usually cited for the argument that categorizations, definitions and labels by themselves are oppressive. For Foucault’s central examples of gender and sexual identity, this is quite convincing of course, but it’s a complex discussion outside my expertise.

*

For the definition of games, I think it’s important to note that games, like corporations, just aren’t people. Yet we can still have situations where the games of certain communities are excluded because they don’t fit a particular conception of games (some people feel this is happening with Twine games).

I think we also often gravitate to comparing the definition of art with the definition of game. In a 1956 paper on “The Role of Theory in Aesthetics”[3], Morris Weitz points out that many definitions of art are evaluative, such that it makes no sense to claim that, “This is a work of art and not (aesthetically) good”. I.e. the definition of art is often a definition of good art. Compare this to most game definitions, for which it would be perfectly possible to claim that something is a game, but a bad one.[4]

*

Having a definition of, say, a particular historical model of games does not force you to use it to prescribe what future “games” should be like. It’s the other way around: by pointing to our unstated expectations, we can identify ways to make something new. I often use this exercise with students: describe your expectations for games, video games, mobile games, free-to-play mobile games. Now try going through the expectations one by one and consider how to break them. Definitions are generative and productive.

*

I think the truth is that by putting forth definitions such as this one, it becomes possible to discuss all kinds of important things. We can discuss cultural expectations, change, we can we can point to new ways of making games, we can discuss historical controversies. By discussing definitions, it becomes straightforward to be explicit about conventions and criteria for inclusion/exclusion in something like game festivals. If we don’t talk about these things, we can easily end up maintaining unstated and limiting conceptions of games.

The question is not as much whether to have a definition, but what kind of definition, and what we are going to use the definition for.

Notes

[1] Anat Biletzki and Anat Matar, “Ludwig Wittgenstein,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta, Spring 2014, 2014, http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/wittgenstein/.

[2] Anil Gupta, “Definitions,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta, Summer 2015, 2015, http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2015/entries/definitions/.

[3] M. Weitz, “The Role of Theory in Aesthetics,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 1956, 27–35.

[4] The main exception is Sid Meier’s statement that “A game is a series of interesting choices”. This is a definition of a good game.