This is my eleventh monthly Patch Wednesday post where I discuss a question about video games that I think is unanswered, unexplored, or not posed yet. I will propose my own tentative ideas and invite comments.

The series is called Patch Wednesday to mark the sometimes ragtag and improvised character of video game studies.

The word formalism has resurfaced again in discussions around video games (here, here, here). This post is not specifically about that discussion, but I would like to use the moment to discuss the idea of formalism in video game studies.

First: Formalism, formalist and more specifically anti-formalism have appeared a number of times in discussions around video games, but with often contradictory meanings. With this post I am attempting to give an overview of the terms’ history in relation to video games.

tl;dr The term “Formalism” has no particular set meaning and its politics are wildly contradictory. Its only universal meaning is the derogatory function of denouncing someone as theoretically, morally or politically bankrupt. But there are many interesting discussions in the details.

Let us go through the history and number the anti-formalisms we meet. Warning: If you are not familiar with every discussion, this will be quite compact. I identify 8 variations of anti-formalism, the 7 of which relate to video games. Here is the list.

- Formalism #1: Experiments are formalist. Don’t make experimental art – that would make you an enemy of the people

- Formalism #2: Experiments are formalist. Form, experiments or aesthetics are anti-political (or anti-progressive)

- Formalism #3: Experiments are formalist, and experiments are a way of fighting against oppression, and for letting marginalized voices speak

- Formalism #4: Defining things is formalism, and formalism is a way of locking down video games to prevent experimentation

- Formalism #5: Formalism = looking at game rules to the exclusion of looking at story, experience, meaning

- Formalism #6: Formalism = assuming that game meaning comes exclusively from the game rules

- Formalism #7: Formalism = looking at game design to the detriment of looking at players

- Formalism #8: Formalism = game definitions as stifling + focusing too much on rules

Formalism #1: Experiments are formalist. Don’t make experimental art – that would make you an enemy of the people

The history of anti-formalism really starts with Shostakovich and the 1948 Khrennikov decree in the Soviet Union (I’ve written about it here), according to which composers should stop making formalist (i.e. experimental) music.

Khrennikov reported that people “all over the USSR” had “voted unanimously” to condemn the so-called formalists and let it be known that those named in the decree were now officially regarded as little better than traitors: “Enough of these pseudo-philosophic symphonies! Armed with clear party directives, we will stop all manifestations of formalism and decadence.”

“Formalist” and “formalism” in this case meant anything experimental, and anything non-sanctioned by the regime. Fun fact: Shostakovich wrote a piece called Anti-Formalist Rayok (text here) making fun of a committee meeting about stamping out formalism in music. “O let us love all that’s beautiful, charming, and elegant, let us love all that’s aesthetic, harmonious, melodious, legal, polyphonic, popular, and classical!”

This is the original variation of anti-formalist thought, and I think this is the one whose echoes we are still hearing. It is clear that we can divide this in to some subthreads, but this is the source of the baseline air of accusation that is present when someone denounces someone else as formalist.

It’s not much of a stretch to see the relation between Soviet-era anti-formalism and other types of conservative attempts at preventing art experimentation.

Formalism #2: Experiments are formalist. Form, experiments or aesthetics are anti-political (or anti-progressive)

This is a common extrapolation of formalism #1: don’t play around with form, just state your politics in a well-known format. Similarly, from a theoretical standpoint: don’t analyze form, just analyze politics (or lived experience).

In prescriptive variations, this can be perceived as quite stifling. Those who lived through 1970’s will often, regardless of their political persuasion, talk about how oppressive the atmosphere could be, with constant requirements that all aspects of culture should be subservient to dominant political ideas. I am not saying that this necessarily applies to the criticisms I just mentioned, but it is a mode of thinking that has been used to such ends.

Of course, there are particular stories concerning (for example) painting, where (it is usually said) formalist art criticism hailed abstract expression as the highest form of painting, thereby concretely focusing on form to the exclusion of other issues. Such as, say, representation, politics. (Ian Bogost also discusses the broader history of the term here.)

Formalism #3: Experiments are formalist, and experiments are a way of fighting against oppression, and for letting marginalized voices speak.

If we consider that the Khrennikov decree was written under Stalin, then anti-formalist thought can also be seen as a way of protecting the powers that be against ambiguity and new voices speaking. To me, this speaks to my discomfort that some committee, however nice, should decide what experiments we are or aren’t allowed to use.

Formalism #3 is therefore completely contradictory to formalism #2, because experiments in form are assigned a completely negative role in #2, but a positive role in #3.

I recently wrote about how magic realism was interpreted as a way of saying what could not be said in traditional novel form. Rushdie says:

El realismo magical, magic realism, at least as practised by Márquez, is a development out of Surrealism that expresses a genuinely ‘Third World’ consciousness.

The recent wave of Twine games is distinctly formalist in this sense: finding new form for games to express what cannot be expressed in traditional game form.

Formalism #4: Defining things is formalism, and formalism is a way of locking down video games to prevent experimentation

Here formalism/formalist are not used to describe particular works or creators, but are instead applied to theorists:

In the so-called “Zinesters vs. formalists” debate (summarized at the bottom of this post), some people, especially in the Twine community, felt that their work was being excluded by formalists (mostly identified as Raph Koster) who were applying narrow definitions of what games are.

In the slightly different context of Jamin Brophy-Warren’s PBS show, I was also identified as a formalist (though not in a bad way) for having made a video game definition. This is a tad more subtle. “Formalist” may be a misnomer in this case, given that has an uncertain relation to any previous uses of the term.

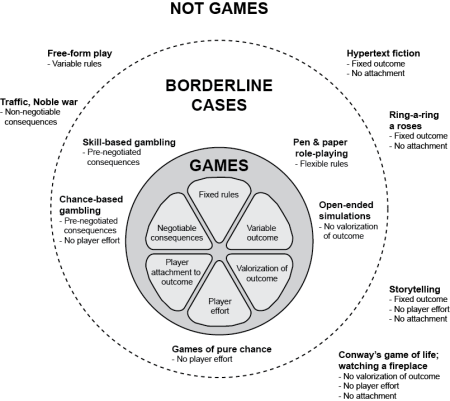

As for the content of that discussion, I do think there is a distinction between is and aught: to identify historical cultural expectations for things called “games” (as I mostly do at least, hence the name “classic game model”) is very different from claiming that this should be used to evaluate or exclude experiments. I do also find that identifying expectations and conventions are a great way to generate new ideas and experiments. And I have a deep-seated hunger for game experiments.

The flip side of it is that nobody is really that aesthetically inclusive anyway: no “game” festival is going to include a word processor in the competition lineup, so isn’t it preferable to ask ourselves if we have criteria than to pretend that we don’t? (Writing this does make me consider whether you could make a mystery game that was basically a modified version of Libreoffice.)

Formalism #5: Formalism = looking at game rules to the exclusion of looking at story, experience, meaning

This is at least how I interpret Janet Murray’s 2005 DiGRA keynote (with its wonderful “mind of winter” metaphor):

According to the formalist view Tetris can only be understood as a abstract pattern of counters, rules, and player action, and the pattern means nothing beyond itself, and every game can be understood as if it were equally abstract. … To be a games scholar of this school you must have what American poet Wallace Stevens called “a mind of winter” ; you must be able to look at highly emotive, narrative, semiotically charged objects and see only their abstract game function.

Again, formalists are theorists, and in this case they emphasize rules structures to the exclusion of everything else.

Note that ludology and narratology are equally formalist according to some views (se #7 below).

Formalism #6: Formalism = assuming that game meaning comes exclusively from the game rules

This is what Miguel Sicart goes up against in Against Procedurality: the idea that game meaning comes exclusively from game rules (rather than from graphics, story etc..), and in a completely deterministic way.

Formalism #7: Formalism = looking at game design to the detriment of looking at players

TL Taylor recently tweeted a series of quotes from what she considers criticisms of formalist video game theory, let me cite a few:

(written by John Dovey and Helen Kennedy in 2006) “As already indicated, these ‘rules’ shape and structure our experience of a game to a greater or lesser degree, but they do not inevitably determine our whole experience. […] These kinds of activity and experience [cheating and mods] cannot adequately be accounted for by a reliance solely on structural or formalistic accounts of games.”

(Jenny Sunden in 2009) “The tension between these two directions in game studies, between games as mechanical-aesthetic objects and games as social practices, echoes the kind of friction between ‘playing the game’ and ‘being played by the game’ characteristic of any act of game play.”

(TL herself): Running nearly parallel to the familiar track of the classic narratology/ludology framing has been scholarship that sought to understand actual players and their everyday practices, as well as research that considered broader structural contexts and histories at work in the construction of play.

(Mia Consalvo in 2009) “What if, rather than relying on structuralist definitions of what is a game, we view a game as a contextual, dynamic activity, which players must engage with for meaning to be made. Furthermore, it is only through that engagement that the game is made to mean”

As you can see, the criticism does not concern rules or definitions as such, but rather the assumption that game design is able to determine actual use by players. Formalism here therefore is a shorthand for focus on game design, including as story, graphics etc…

The difference between #5 and #7 is that #5 promotes the interpretive tools of the humanities, while #7 promotes a social science perspective.

Formalism #8: Formalism = game definitions as stifling + focusing too much on rules

Which brings us to the present day. I see the current discussion (here, here, here) as being a combination of Formalism #4 (game definitions as stifling) and Formalism #5 (focusing too much on rules). This is one of the reasons why it has been a confusing discussion: different things were meant when people said “formalism”.

Conclusion: Which formalism is right for you?

Short answer: none. It’s a term with many contradictory meanings & politics and lots of bad historical baggage. It’s also not conducive to discussion.

Here are some names for the fallacies we are often guilty of in these discussions.

- You are x. This is probably not as conducive to discussions as “is it possible that you are overemphasizing x“?

- Counterfactual generalization by point sample: generalization made explicitly without considering whether it is true, i.e. saying that “a excludes looking at b” even though there is a chapter on b immediately following the chapter on a.

- Graduate luck: The amazing stroke of luck when your graduate studies just happen to be in the theoretical tradition that is superior to all the others. (We have all been there.)

- Exclusion by proxy: arguing that a perspective you dislike is exclusionary of other perspectives and therefore has to be excluded.