Over the summer, I finally succumbed to peer pressure and got myself an iPhone.

As a game platform, I find it interesting not for the high-budget games like Super Monkey Ball (disappointing) or Hero of Sparta (yawn), but for the strange off-beat games.

Take, for example, Enviro-Bear. You have forgotten to prepare for winter and must collect food and get back to your cave before winter comes. In a car. Avoiding the other cars, also driven by bears.

Take, for example, Enviro-Bear. You have forgotten to prepare for winter and must collect food and get back to your cave before winter comes. In a car. Avoiding the other cars, also driven by bears.

There is something to be said for the pairing of the slick hardware of the iPhone with the crude graphics of a game like this. Nintendo probably wouldn’t have approved this on the DS.

The app store is great in making such content accessible on your phone, but it has two major issues:

1) Organization: The in-phone app store remains pretty crude by being organized around top seller lists. This strongly favors hits, pushes prices to the bottom, and makes it harder to sell niche content. A simple fix would be to integrate an Amazon-style recommendation system. Then I could be recommended games that I would actually enjoy rather than forking out money for the next Hero of Sparta.

2) Fear of Objectionable Content: A string of app rejections. For example, Trent Reznor’s app rejected due to “objectionable content” (the F-word as they say here). Of course, you can buy “objectionable” songs (the same song in fact) on iTunes, so this is a simple double standard.

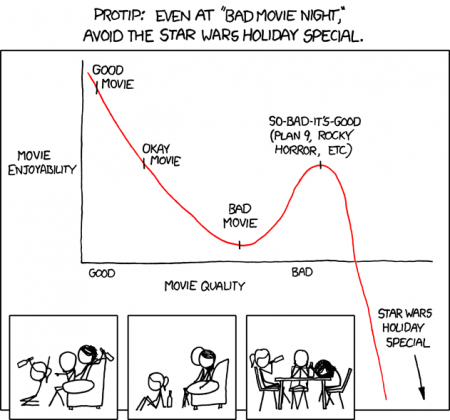

Why assume that games (and applications) should never be objectionable?

We understand, and Apple understands, that media may have content that is objectionable to some people. In music. In books. In art. Film. But video games are still being hampered by the strange idea that they, somehow, should be the only clean and non-objectionable art form in existence. This shows up in Apple’s rejections. It shows up in the fact that the platform holders continue to decide what is published. It shows up in the fact that Australia does not have a mature rating for video games.

And yes, I do think it is holding video games back, as an art form.

From the not-so-

From the not-so- A Casual Revolution is my take on what is happening with video games right now:

A Casual Revolution is my take on what is happening with video games right now:

Take, for example, Enviro-Bear. You have forgotten to prepare for winter and must collect food and get back to your cave before winter comes. In a car. Avoiding the other cars, also driven by bears.

Take, for example, Enviro-Bear. You have forgotten to prepare for winter and must collect food and get back to your cave before winter comes. In a car. Avoiding the other cars, also driven by bears.