This is my second Patch Wednesday post where I discuss a question about video games that I think is unanswered, unexplored, or simply not posed yet. I will propose my own tentative ideas, and invite comments.

The header does sound a bit like Ash Wednesday, so we can reaffirm our faith in the idea of examining video games, but I also call it Patch Wednesday to mark the sometimes ragtag and improvised character of video game studies. It falls mostly on the day after Microsoft’s monthly Patch Tuesday. Time to patch things up and start again.

Question #2: Do Casual Games still Exist?

It seems a long time ago, but I once wrote a book called A Casual Revolution (2009), where I talked about the expansion of the video game audience, and focused particularly on the downloadable casual games, the Nintendo Wii, and music games.

It seems a long time ago, but I once wrote a book called A Casual Revolution (2009), where I talked about the expansion of the video game audience, and focused particularly on the downloadable casual games, the Nintendo Wii, and music games.

I had picked the most important platforms, genres, and distribution channels of the day. I knew that these things come and go, and they did, quickly. The Wii is all but gone, and the Wii U is doing poorly and not even built around motion controls, and Sony’s Move didn’t take off. Music games are all but dead. Downloadable casual games is not as important a channel as it used to be.

So do casual games still exist? Is it still an important category? Since publishing the book, I have liked to tell the big-picture story like this (some of this material was also published in the Korean translation):

There was a period of time, roughly from 1980 to 2005, when we knew what video games were. Video games, we knew, followed a standard model: they were fairly involved activities that you had to spend hours and days to play; they were mostly sold in boxes; new games and game platforms were always promoted on technically better graphics; games were mostly targeted at young males. (We knew, of course, that video games were in actuality played by men and women, young and old, but most video games were still targeted at the traditional “gamer” demographic.)

This standard model fell apart around 2006. At that time, video games distributed online became a major factor; the industry woke up to the fact that women and adults are perfectly interested in playing video games; the most successful console of the generation, the Nintendo Wii, wasn’t even promoted on better graphics, but on a new easy-to-use interface; game developers began experimenting with games that could be played in shorter sessions.

When I originally wrote the book, these changes were most clearly visible in music games, the Nintendo Wii, and downloadable PC games. Since then, the casual revolution has continued. The trend is still towards new distribution models, a broader audience, and video games arriving in new shapes and sizes, only the revolution has moved on to new platforms. Much of today’s innovation is happening in games for cell phones where the selling point is rarely the latest graphics, but much more about style, about game designs that fit into the lives of players. Furthermore, games on social networks are showing new ways in which games can be integrated into our lives, allowing us to keep contact with distant friends, still playing through every busy day. Games find a way.

The Tally

To score my own efforts, the book was correct in seeing the casual revolution as an expansion of the audience, and as a series of design principles that made games available to people who would not otherwise play them. I was also correct in seeing it as a change that would continue to reshape the industry.

In retrospect, the book put too much emphasis on particular platforms (notice the controller on the cover), but it is hard to tell such a story in the abstract.

I also described five principles of casual design (this was inspired in part by conversations with many industry people):

- Positive fiction. Set in a situation you would actually want to be in.

- Usability. Easy to use.

- Interruptible and with low required time investment.

- Difficulty that can become high over time, but always with lenient punishment for failure.

- Juiciness. Excessive supportive feedback to the player.

Does this still hold? Time investment remains the most important barrier to play, and most of the principles hold, with significant footnotes for 1) and 4):

1) Positive fiction: Plants vs. Zombies showed that you can make a mass-audience game that is gross and violent, if the representation is sufficiently cute.

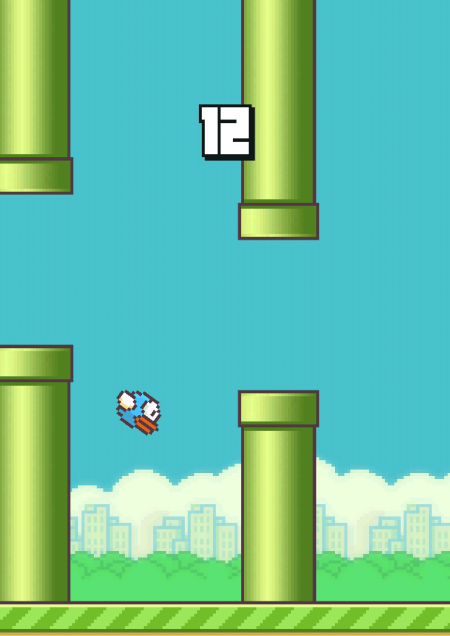

4) Punishment: with the recent popularity of Candy Crush, Canabalt, Super Hexagon or Flappy Bird, some of the casual-hardcore distinction seems to collapse. “Casual Games” were never just easy, even if they have sometimes been discussed as such. But the endless runner genre is hugely successful, even though it actually punishes players strongly for failing since you go back to the beginning. This is, in many games, just offset by an accumulation of powerups and resources.

What I failed to see here was the way in which high difficulty and punishment can actually lower the required time investment. Super Hexagon or Flappy Bird are so difficult that the required time investment becomes minuscule, and the individual game session is only a few seconds long.

Things also not predicted:

- That the Wii would fade out so quickly.

- That the Xbox One and PlayStation 4, though being delayed as predicted, would still be promoted on better graphics, and would sell well (at least initially).

- The popularity of smart phone and table gaming.

*

Ironically, the casual revolution in video games is making the term “casual games” less central that it may have been: the audience has become larger and more diverse, and the distribution channels are becoming less distinct. It used to be that the big-budget “hardcore” games could be found on consoles, and the small-budget “casual” games could be found the casual sites, but this is less clear-cut than it used to be, so where do some of recent hits even belong?

So this is the big picture: we used to know what video games were, and now we don’t. We remain in a space of uncertainty: video games can be so many more things than we thought they could, and they continue to change and confound our expectations.

It seems a long time ago, but I once wrote a book called

It seems a long time ago, but I once wrote a book called