This is my fifth Patch Wednesday post where I discuss a question about video games that I think is unanswered, unexplored, or not posed yet. I will propose my own tentative ideas and invite comments.

The series is called Patch Wednesday to mark the sometimes ragtag and improvised character of video game studies.

What do games mean? There is a lot of good work on meaning and values in games, of course, but I think there is a very simple question that has not been fully addressed. (When I talk about “mean” here, it is primarily in the sense of a game making a normative statement about what is good/bad.)

If something is present in a game, is that a statement to the effect that what happens in the game is good and ought to be present in regular life?

Certainly, negative media commentary about video games tends to follow a very simple form, assuming that if something happens in a game (say, war), this is a ringing endorsement of war in general. In table form, it would look like this:

That is obviously too simple. A pro-war game will say that war is good, but an anti-war game will say that war is bad. That the endorsement view is too simple doesn’t let video games of the hook, it just means that there is more to the discussion, as there are at least two different interpretations of similar game events. The classic example is Monopoly, where the game structure was originally designed to criticize land ownership (in The Landlord’s Game), but in Monopoly this is usually interpreted as an endorsement of land ownership and capitalism. In matrix form:

|

This is good |

This is bad |

| Event |

Hoarding property |

Hoarding property |

But there is an additional possibility. If we think of sci-fi games or any game which does not claim to represent the world as it currently is, the game can also be making statements about possible futures (say, the fight between humans and machines). It follows that a game can either say something about the current state of the world, or about a possible future (or the past). Consider the example of whether money buys political influence, and consider a game in which this is the case. This could then be taken in four different ways: Saying that 1) this is already the case (and it is bad), 2) this is already the case (and it is good), 3) this is not yet the case (and it would be bad), 4) this is not yet the case (and it would be good). (Remember that some people do believe that this is good.) This is the basic interpretation matrix:

|

This is good |

This is bad |

| How it is |

Money buys political influence |

Money buys political influence |

| How it could be |

Money buys political influence |

Money buys political influence |

The very hard question, then, is how we interpret a particular game such as Grand Theft Auto V. I may have sometimes been too keen on making the “it’s more complicated than that”-argument and leaving it at that. So let’s go on.

The enjoyment of bad things

The problem with GTA V probably is that while it on some level can be seen as making social commentary about violence, race, gender, and politics, arguably placing it in the how it is / this is bad square (given that all characters are anti-heroes), it just does that in an uncomfortably leery, consistent and celebratory fashion. So the interpretation matrix is rather like this, where the game at least part of the time seems to be signaling the right thing, but that it is hard not to feel that there is a voice in the game screaming “AWESOME!” at the in-game violence, sexism and racism. Matrix:

|

This is good |

This is bad |

| How it is |

GTA V world |

GTA V world

(“IT’S ALSO AWESOME!“) |

| How it could be |

GTA V world |

GTA V world |

This doesn’t quite end it though. In reception studies (say Janet Staiger’s Perverse Spectators) one discussion concerns what we can call interpretation-by-proxy. I.e. “I am a good person with all the right morals, critical faculties and so on, but the actual audience for this movie/game/book obviously lacks these qualities and will be brainwashed and interpret things very differently. And I will make judgments based on my prejudices about that naive audience “.

What we can say about GTA V is that a suspicious amount of energy and care has gone into making a particular game world with events that we would at any time say we are against, but which are also meant to be enjoyable (in a broad sense) when we play the game. Of course, this is a criticism to be leveled at any kind of art or discussion about unpleasant subjects – that they end up aestheticizing what they are supposed to be against. (See also the PPPS below.)

So how can we tell if there is such an “AWESOME!” model player of GTA V, and that it isn’t just us being prejudiced about a game audience in the same way that academics have traditionally been prejudiced about the television, romance novel, game audiences? The short answer is that we cannot simply assume that we are personally superior to the imagined audience of a given game/movie/novel.

In the end, then, I think the problem with GTA V is that it seem to show too much love for its own present/dystopian world. And this is what makes us skeptic about the meaning of the game; about what value the game is assigning to its content.

This is what the interpretation matrix is for: by looking at the meaning of a game as an interpretation matrix, we can to take a step back and think more broadly about possible, and sometimes conflicting, meanings.

***********

PS. I don’t think I have seen these interpretation matrices before, but it seems like an obvious idea, so I may be wrong.

PPS. In A Year with Swollen Appendices, Brian Eno describes the impossible futures-game, where participants have to describe futures that can never take place. One example is people with different astrological signs waging war against each other. This is the “how it could not possibly be”-variation, which is quite rare.

PPPS. Susan Feagin talks about (“The Pleasures of Tragedy“) that we may enjoy tragedy for the fact that it makes us feel good about our own moral standing, “We find ourselves to be the kind of people who respond negatively to villainy, treachery, and injustice. This discovery, or reminder, is something which, quite justly, yields satisfaction.” We probably associate this with the too keen and PR-minded celebrity who is into good causes, but of course it could also be that we are like that ourselves. In matrix form:

|

This is good |

This is bad |

| How it is |

Violence |

Violence

(“This belief makes me a good person!”) |

| How it could be |

Violence |

Violence |

The king in Checkers – but this is not what I meant, since the stacking of two pieces is just a convenient way to signal a special piece, rather than an element of the gameplay. So merging is to be understood in a gameplay-sense.

The king in Checkers – but this is not what I meant, since the stacking of two pieces is just a convenient way to signal a special piece, rather than an element of the gameplay. So merging is to be understood in a gameplay-sense. New winner (thanks to Marc Majcher): the 1990 Darwin’s Dilemma.

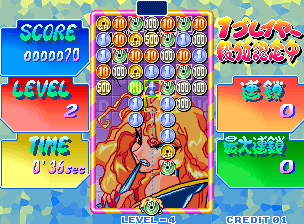

New winner (thanks to Marc Majcher): the 1990 Darwin’s Dilemma.![DBTPlay07[1]](http://www.jesperjuul.net/ludologist/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/DBTPlay071.jpg) his was easy: I immediately recognized the slide to combine control of Denki Blocks (2001). In Denki Blocks, objects don’t merge to occupy a shared space, but rather become stuck to each other.

his was easy: I immediately recognized the slide to combine control of Denki Blocks (2001). In Denki Blocks, objects don’t merge to occupy a shared space, but rather become stuck to each other.