This is my fourteenth monthly Patch Wednesday post where I discuss a question about video games that I think is unanswered, unexplored, or not posed yet. I will propose my own tentative ideas and invite comments.

The series is called Patch Wednesday to mark the sometimes ragtag and improvised character of video game studies.

What is a game?

One of the joys of having been around for a while in game studies is to see certain arguments repeatedly go in and out of fashion. It’s not as much cyclical (since we never quite return to a place we have been before), but rather that old arguments come back, donning new garb and meaning something somewhat different than they used to.

At the very good recent DiGRA conference in Lüneburg, many speakers stated how they were “not interested in definitions”. After initially trying to question that sentiment, I decided to rather note some of the recent history of game definitions. Please pardon the self-indulgence as I return to my own earlier work.

*

As you recall, Wittgenstein argued against trying to define games (or rather the German Spiel), saying that we should not look for an essential core, but see the myriad ways in which the word is used, only connected by family resemblances. Or rather: in common interpretations[1], games was just an example for Wittgenstein – what he criticizes is the attempt at looking for definitions in the first place, for any word. So Wittgenstein’s argument is not specific to games at all.

The thing, of course, is that Wittgenstein is not trying very hard to find any commonalities in the activities he is describing (board-games, card-games, ball-games, Olympic games). At the very least, they do seem to be semi-repeatable activities performed by humans…

*

And then – certainly there is a general post-structuralist attitude common in the humanities and social sciences today, and which I was trained in myself. So when thinking about video games, it was interesting to try to make game definitions, in part because you are not supposed to!

In my 2003 paper The Game, the Player, the World: Looking for a Heart of Gameness I came up with what I called The Classic Game Model:

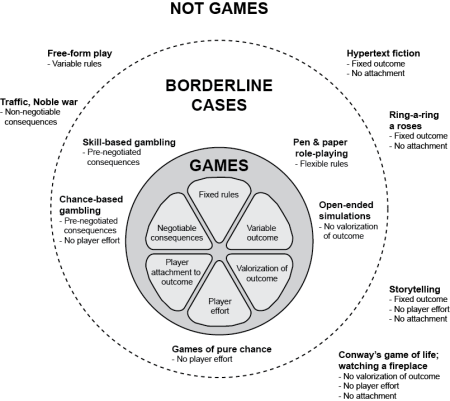

A [classic] game is a rule-based formal system with a variable and quantifiable outcome, where different outcomes are assigned different values, the player exerts effort in order to influence the outcome, the player feels attached to the outcome, and the consequences of the activity are optional and negotiable.

It also came with an illustration, pointing to the “games” where we tend to disagree about whether or not they are games:

What kind of definition?

I called this a definition, but what does that mean? It does not cover all possible uses for the word “game”, or even a (harder to define) preexisting notion of “game”. Philosopher Anil Gupta distinguishes between different types of definitions, let me mention three candidates[2]:

- Stipulative: “imparts a meaning to the defined term, and involves no commitment that the assigned meaning agrees with prior uses (if any) of the term”.

- Descriptive: “like stipulative ones, spell out meaning, but they also aim to be adequate to existing usage.”

- Explicative: “An explication aims to respect some central uses of a term but is stipulative on others. The explication may be offered as an absolute improvement of an existing, imperfect concept. Or, it may be offered as a “good thing to mean” by the term in a specific context for a particular purpose.”

This explains it better than I could: my game definition is not about covering all existing usages (descriptive), but it is still invested in previous uses (not stipulative).

Hence, my definition is explicative: it is intended as an improvement over an existing concept, but doesn’t aim to replace or supersede existing or future uses. It is rather a definition for the particular purpose of identifying points of contention around games.

An open definition

It’s an explicative definition, but it is also open in two ways:

- It is a “classic model”: it describes a model that was dominant a particular period in time, and this makes it useful for noticing when our conception of games By now, it seems clear that Sims and Sim City are games, but it wasn’t the case when they came out. Similarly, we can discuss why some people reject Proteus as a game.

- The definition is open to disagreements about borderline cases (gambling, P&P RPG, open-ended simulations).

Definitions: Limiting or liberating?

As I said, I think we are in a general post-structural epoch wherein it is easy to think of definitions as limiting, or even dangerous. The latter view arguably comes in part from Foucault, usually cited for the argument that categorizations, definitions and labels by themselves are oppressive. For Foucault’s central examples of gender and sexual identity, this is quite convincing of course, but it’s a complex discussion outside my expertise.

*

For the definition of games, I think it’s important to note that games, like corporations, just aren’t people. Yet we can still have situations where the games of certain communities are excluded because they don’t fit a particular conception of games (some people feel this is happening with Twine games).

I think we also often gravitate to comparing the definition of art with the definition of game. In a 1956 paper on “The Role of Theory in Aesthetics”[3], Morris Weitz points out that many definitions of art are evaluative, such that it makes no sense to claim that, “This is a work of art and not (aesthetically) good”. I.e. the definition of art is often a definition of good art. Compare this to most game definitions, for which it would be perfectly possible to claim that something is a game, but a bad one.[4]

*

Having a definition of, say, a particular historical model of games does not force you to use it to prescribe what future “games” should be like. It’s the other way around: by pointing to our unstated expectations, we can identify ways to make something new. I often use this exercise with students: describe your expectations for games, video games, mobile games, free-to-play mobile games. Now try going through the expectations one by one and consider how to break them. Definitions are generative and productive.

*

I think the truth is that by putting forth definitions such as this one, it becomes possible to discuss all kinds of important things. We can discuss cultural expectations, change, we can we can point to new ways of making games, we can discuss historical controversies. By discussing definitions, it becomes straightforward to be explicit about conventions and criteria for inclusion/exclusion in something like game festivals. If we don’t talk about these things, we can easily end up maintaining unstated and limiting conceptions of games.

The question is not as much whether to have a definition, but what kind of definition, and what we are going to use the definition for.

Notes

[1] Anat Biletzki and Anat Matar, “Ludwig Wittgenstein,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta, Spring 2014, 2014, http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/wittgenstein/.

[2] Anil Gupta, “Definitions,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta, Summer 2015, 2015, http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2015/entries/definitions/.

[3] M. Weitz, “The Role of Theory in Aesthetics,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 1956, 27–35.

[4] The main exception is Sid Meier’s statement that “A game is a series of interesting choices”. This is a definition of a good game.

Touching Wittgenstein is great, thank you for that, Jesper.

It is important to recognize that in his Philosophical İnvestigation, he aims to criticize referential language theories. That’s why he is in particular criticizing Saint Augustine and the roots of nominalism. The problem with an essential core is that you stick with a dominant definition for a word and tend to label everything that seems to deviate from this definition as the “non” of this word. You will remember how you yourself were writing about games in this nominalist way in your article on emergent games Only when you arrived at a specific definition of what a game is – that is, giving privilege to a specific definition – could you claim that adding narratives would destroy them.

This is the problem of the reference point. You need a reference point to start with, so that others can be articulated around it, but when such initial reference point is treated as if it were an ontological essence, you easily find yourself glued to it and treat is as a fact, an object, rather than a lingual category against which objects are basically indifferent. In On Certainty, Wittgenstein tries to formulate an approach that has no reference points, but rather tries to capture this “centre” as an axis that appears as the result of somewhat chaotic yet patterned movements. So basically he means to say there is no fixed centre, but rather a multitude of movements whose combined actions make such centre look like it really exists. This lends itself excellently to the idea that the “centre” constantly shifts, disappears, reappears etc as scholars discuss what a game “is”. The ultimate issue here is that game studies must tackle the word “is” itself, for it becomes clear at this point that the notion of game will constantly shift as new concepts are introduced and the constellation of reference points undergoes transformation. It also allows us to throw up critically and politically motivated questions for one can now ask why in the early Ludology days it was so important to re-define “games” (the search for a new reference point of the whole discipline) and what the motivations were behind the movement that made such centre suddenly look like the only reality about games. One can also ask now why scholars prefer to stay away from making such definition as it happened to be the case in Lüneburg.

You are of course right that his Philosophical Investigations was not about games per se. The topic were languages, in particular meaningful experience of the material world. Much earlier, in his Tractacus, he himself assumed a world with given language categories that simply reflect the world order. This idea could go so far as to say that you can have an objective logics based method to describe the world as it is, in its reality. But after he left Britain, he must have realized that the relation between words and things isn’t that simple, and that exactly in this view of language there is a barrier that obscures the much more complicated relationship between them. Games were a great analogy for Wittgenstein to show the richness of languages, and also to explore the relationship between languages and the world. The spectrum of games is indeed so broad that you often find nothing in common between two particular games, yet you put them under the same umbrella term “game” due to what he calls “family resemblances”. But then, once you stick with a particular definition of what a game is, you go so far as to ignore many of the existing resemblances, simply calling it “not a game”, because it violates a self-proclaimed attribute that you have announced as the ultimate measure of what a game is. It is interesting to note that he says the same for language when he criticizes St. Augustine for narrowing down languages to what linguists call natural languages. There are two paragraphs were he first slams definitions of games that restrict them to board games (he would have slammed your notion of the formal game for almost the same reason), and second where he slams definitions of language that restrict them to natural languages. In both cases his struggle is against referential language models and nominalism.

This move is clearly an attempt to put into question a ontology that mistakes words for things, even judges things from the perspective of certain privileged definitions. Not only is he not trying very hard to find any commonalities, his goal is exactly to show that no matter how hard you try, you will always come across something that invalidates your carefully established taxonomy. Exactly Foucault’s point some 20 years later.

The responsibility that finds us all the sudden is then not simply to think that it doesn’t matter anyway to define what games are, but rather to see that defining not is still a definition, and one should wonder why we prefer such a broad “center” for games while only a decade ago we ripped each other almost into pieces when we all were keen to define that one fixed center that games are supposed to be.

Your graph is very detailed and cool, but just look at the anthropologists and folklorists of the 20th century, especially during the 50s and 60s. Some have so broad taxonomies, they include under the category of games jokes, theatre plays, riddles etc, and yet they do not manage the exhaust the richness; they still have an “other” category, so as to make their taxonomy work. Something must remain unnamed or swept under the carpet to make it look stable. In the late 90’s and early 2K’s, story was one of the things that needed to remain unnamed in order to make the new game definitions look somewhat stable. It’s only now, that after this re-centering around “gameplay” as the core of games, we feel now safe to move away from strict definitions of games and try to be more open about our taxonomies. And so many variations of game types come in today, you realize that your “centre” has now almost no meaning. Today, Ludology is a discipline that studies types of games that it ignored when it strived to set itself up as a respected discipline.

When you say your definition is explicative you basically say it is a particular movement among others to make an axis/centre appear. That’s a great approach in my humple opinion. Why I still, after so many years, criticize your early articles is that you definitely had some sort of a nominalist phase when you struggled with other disciplines to -forgive me for saying that- “possess” games. You now speak from a loosened position, but when you speak of borderline cases, you still seem to start from a specific privileged reference point for the word game and the objects that this word refers to. I suggest to think of the Word game not as something that points to an ontology of games, but rather to certain industrial or cultural practices that popularize certain types of games and gameplay stronger than others, causing certain centres that we then assign our own conceptual centres to. In other words, the things we refer to when we use the word game, are again “centres” that appear as “facts” to us due to the variety of movements and motivations in the industry that hold those centres up as such. It is therefore very important that we, as game researchers, recognize that the centres that we mistake for ontologies are caused by a constant movement in culture and society. When we are old and about to die, games will mean something completely different. An ongoing archeology of the concept is therefore much more important than to constantly attempt to come up with one all-encompassing definition.

The architect Bernard Tschumi says he wished to be exactly on the border, not inside, nor outside it, rather someone who moves with it as it shifts and make it shift with his own ideas and inventions, never allowing a center that could be mistaken for an ontology to crystalize. That is what some experimental game designers try to be today. I think that the whole case of Celia Peirce, when linking games to art was to do this. I think Ian Bogost, in his very own way, is doing this. And I think it would be great if we have more borderline-people, not only in Academia, but in the industry and among independent game devs as well. The use of this would be that we never allow a single definition of games to rule the discipline and cultural production.